Indeed, its boss, Jeff Bezos, was recently dragged before the US Congress and had to defend his firm from hostile questioning. Is monopoly such a bad thing anyway?Īmazon is one of the companies charged with unfairly exploiting its dominant position to crush competition and hence harm customers. So increased global competition and greater national concentration may be two sides of the same coin – “growing global competition may force unproductive firms to exit and top firms to consolidate on their best products”. They find that when competition from foreign imports is included, the overall level of competition may in fact have intensified rather than fallen – even if the number of firms from the home country entering the market falls. As a 2019 paper by Alessandra Bonfiglioli, Rosario Crinò and Gino Gancia for the Centre for Economic Policy Research notes, all the existing evidence for the increase in industrial concentration and the fear that this will usher in a new era of monopolies has been based on national data. In any case, the rise in industrial concentration may not be all it appears to be. If the causes are unclear, then there’s no way to be confident about what the correct policy response should be. It might reflect a reduction in competitive intensity, but it might equally be the outcome of intense competition. A roundtable discussion of the subject by experts, hosted by the OECD group of wealthy nations in 2018, concluded that although market power did indeed appear to be rising in many countries, the causes were unclear.

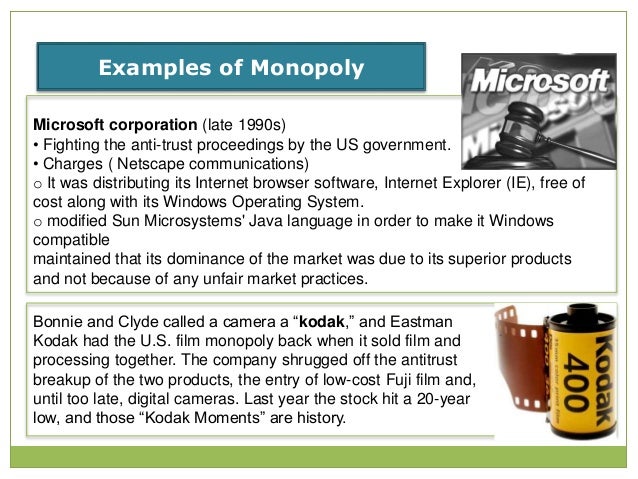

A company operating in a market economy might look like a monopoly “under myopically static analysis”, but a broader and historical view will reveal that even very large, dominant companies face intense competitive pressure – whether from the fear of potential competition from new entrants eyeing their high profits or from competitors offering products and services of a different but nevertheless substitutable kind or from losing customers altogether, should they decide they’d rather do without what is being offered.Īnd if that’s what first principles tell us, there are plenty of reasons to be sceptical about what the real-world data are showing, too. As Edmond Bradley, a writer for the Mises Institute, put it back when Microsoft was the monopolistic bogeyman in the early 2000s, “the fear of industrial concentration is the last refuge of socialist theory” and the idea that governments must step in to save us from it is “wildly incorrect”. A sounder tradition in economics would lead us to be cautious about the claims from first principles. The case for the defenceĪre Marx and his mainstream followers correct? The answer, as ever, is – it’s complicated. If rising concentration and monopolies are a problem, it’s one that seems set to get worse. Low interest rates may also contribute, as bigger companies are in a better position to get hold of cheap credit and invest it in expansion. The combined effect will be to push smaller firms out of business, quenching the fires of creative destruction, and for the well-connected, better organised larger companies to obtain all the government cash and bolster their already dominant position.

The response of governments to the coronavirus pandemic has led to a huge economic crisis, and their response to what they have caused is to throw money at it. They suggest that such policies might help to slow the rise of inequality and the growth in debt, and make financial crises less likely.

The authors call for policies that will redistribute wealth to the poor, perhaps by gradually raising the tax on dividend income from zero to 30%.

They blame the rising market power of big companies for the decline in the share of wealth that goes to workers, the rise in inequalities of wealth and income, and the growing debt burden. Indeed, “Market Power, Inequality and Financial Instability” – a new paper by Federal Reserve Board economists Isabel Cairo and Jae Sim – argues that the concentration of market power in a handful of companies, and the resulting decline in competition, explains the deepening of inequality and financial instability in the US, as Craig Torres reports on Bloomberg. All the main political parties – particularly in the US, where the problem is deemed to be particularly acute – agree that something must be done to curb the rise of the monopolies, namely that the state should step in and break them up, or at least restrain them. It is not all that easy to find a mainstream commentator, economist, think-tanker or policymaker who will raise a squeak of protest against the idea. Perhaps surprisingly, it is also the mainstream view today. This, at least, was the view of Karl Marx.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)